Caridina spongicola

Harlequin Shrimp

Wissenschaftliche Klassifizierung

Schnellstatistiken

Aquarienbau-Informationen

Über diese Art

Grundbeschreibung

Detaillierte Beschreibung

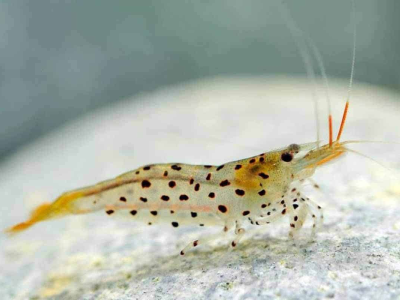

Die Harlekingarnele, ein Mitglied der Gattung Caridina, ist ein hochspezialisiertes Krebstier, das in den alten Seen von Sulawesi, Indonesien, beheimatet ist. Das Verständnis ihres natürlichen Lebensraums ist der Schlüssel zu ihrer erfolgreichen Pflege in Gefangenschaft. Diese Seen zeichnen sich durch außergewöhnlich stabile Bedingungen aus: warmes, alkalisches Wasser mit hohem Mineralgehalt und minimaler Strömung. In freier Wildbahn leben diese Garnelen in einer faszinierenden Beziehung zu Süßwasserschwämmen, auf und in denen sie wohnen und den darauf wachsenden Biofilm abweiden. Daher ist die Nachbildung dieser stabilen Umgebung für jeden Hobbyisten, der versucht, sie zu halten, von größter Bedeutung.

Die Einrichtung eines Aquariums für diese Garnelen erfordert Geduld und Präzision. Ein eingefahrenes, gut etabliertes Becken von mindestens bescheidener Größe ist zwingend erforderlich. Es wird dringend empfohlen, sie in einem reinen Artenbecken zu halten, da ihre spezifischen Anforderungen an die Wasserparameter schwer mit denen der meisten anderen Aquarienbewohner zu vereinbaren sind. Schwankungen von Temperatur, pH-Wert oder Wasserhärte können tödlich sein. Das Wasser muss konstant warm und alkalisch gehalten werden, mit einem stabilen Mineralgehalt. Ein Filtersystem mit geringer Strömung, wie z. B. ein Schwammfilter, ist ideal, da es die sanfte Wasserbewegung ihres natürlichen Lebensraums nachahmt und eine zusätzliche Oberfläche für das Wachstum von nützlichem Biofilm bietet.

Als in Gruppen lebende Tiere müssen Harlekingarnelen in Gruppen gehalten werden, um sich sicher zu fühlen. Eine einzelne Garnele wird permanent gestresst sein und ihr natürliches Futtersuchverhalten nicht zeigen. Sie sind mäßig aktive Bodenbewohner, die ihre Tage damit verbringen, akribisch Oberflächen nach Nahrung abzusuchen. Obwohl sie als Allesfresser eingestuft werden, besteht ihre Hauptnahrung aus Biofilm und Detritus. Ein erfolgreiches Setup wird reichlich Oberflächen wie Steine, Holz und Pflanzen aufweisen, um diese natürliche Nahrungsquelle zu kultivieren. Dies kann täglich mit hochwertigem, für Garnelen entwickeltem Sinkfutter ergänzt werden. Trotz ihrer komplexen Pflegeanforderungen produzieren sie sehr wenig Abfall, was eine minimale Biolast für das Ökosystem des Aquariums bedeutet. Ihre empfindliche Natur und ihre speziellen Bedürfnisse machen sie zu einer lohnenden, aber anspruchsvollen Art, die sich am besten für den erfahrenen Aquarianer eignet, der sich der Schaffung einer präzisen und stabilen aquatischen Umgebung widmet.

Wissenschaftliche Beschreibung

Caridina spongicola ist ein kleines Süßwasser-Zehnfußkrebs aus der Familie der Atyidae, einer Gruppe, die für ihre vielfältigen und oft endemischen Arten bekannt ist. Das Art-Epitheton „spongicola“ bedeutet wörtlich „Schwammbewohner“, was ihre hochspezialisierte ökologische Nische treffend beschreibt. In ihrem natürlichen Lebensraum in den alten tektonischen Seen von Sulawesi, Indonesien, zeigt C. spongicola eine kommensalische oder symbiotische Beziehung zu bestimmten Arten von Süßwasserschwämmen. Die Garnelen nutzen die Struktur des Schwammes als Schutz vor Fressfeinden und weiden den reichhaltigen Biofilm, Algen und Mikroorganismen ab, die seine Oberfläche besiedeln.

Morphologisch zeichnet sich die Art durch eine geringe Adultgröße und eine seitlich abgeflachte (kompressiforme) Körperform aus, die für viele Caridina-Garnelen typisch ist. Ihre Physiologie ist fein auf die einzigartigen limnologischen Bedingungen ihrer Umgebung abgestimmt, die durch hohe Alkalinität, eine beträchtliche Mineralhärte und konstant erhöhte Temperaturen gekennzeichnet sind. Diese Parameter müssen bei Erhaltungszucht- und Haltungsbemühungen ex situ akribisch nachgebildet werden. Die Art weist eine niedrige Stoffwechselrate und einen sehr geringen Sauerstoffverbrauch auf – Anpassungen, die in einem stabilen, oligotrophen Seensystem vorteilhaft sind. Folglich hat sie eine sehr geringe Abfallproduktion, was zu einem minimalen Biolast-Faktor in geschlossenen Systemen führt.

Aus Sicht des Artenschutzes ist C. spongicola auf der Roten Liste der bedrohten Arten der IUCN als „gefährdet“ (Vulnerable) eingestuft. Die Hauptbedrohungen für die Wildpopulationen umfassen die Zerstörung des Lebensraums durch Umweltverschmutzung, Abflüsse aus dem Nickelabbau und die Einschleppung gebietsfremder Arten in das Seen-System von Sulawesi. Auch das übermäßige Sammeln für den Zierfischhandel übt erheblichen Druck auf die verbleibenden Populationen aus. Die Schwierigkeit bei der Nachzucht in Gefangenschaft, gepaart mit den sehr spezifischen Umweltanforderungen, bedeutet, dass der Handel immer noch stark auf Wildfänge angewiesen ist. Dies unterstreicht die Bedeutung nachhaltiger Sammelpraktiken und gemeinsamer Anstrengungen bei der Entwicklung zuverlässiger Nachzuchtprotokolle, um das langfristige Überleben dieser ökologisch einzigartigen Art zu sichern.

Zuchtbeschreibung

Die Zucht der Harlekingarnele gilt weithin als schwieriges Unterfangen und stellt selbst für erfahrene Garnelenhalter eine erhebliche Herausforderung dar. Der Erfolg hängt von der Schaffung einer Umgebung mit außergewöhnlich stabilen Wasserparametern ab, die exakt denen ihres natürlichen Lebensraums entsprechen. Schon geringfügige Schwankungen können die Fortpflanzungsaktivität stoppen oder für den empfindlichen Nachwuchs tödlich sein.

Diese Art gehört zum „spezialisierten Fortpflanzungstyp“, was bedeutet, dass das Weibchen die Eier austrägt, bis daraus vollständig entwickelte, winzige Versionen der Alttiere schlüpfen. Im Gegensatz zu vielen anderen Garnelen, die ein freischwimmendes Larvenstadium haben, das Brackwasser benötigt, findet der gesamte Lebenszyklus der Harlekingarnele im Süßwasser statt. Dies vereinfacht einen Aspekt der Zucht, unterstreicht aber die entscheidende Bedeutung der Bedingungen im Hauptbecken für das Überleben der Jungtiere. Die Unterscheidung der Geschlechter kann schwierig sein; wie bei vielen Caridina-Arten sind jedoch geschlechtsreife Weibchen typischerweise etwas größer und besitzen einen breiteren, runderen Schwanzfächer und Bauchbereich, der zum sicheren Tragen der Eier ausgebildet ist. Männchen sind tendenziell kleiner und schlanker.

Für einen Zuchtversuch ist ein dediziertes Artenbecken unerlässlich. Dies eliminiert Bedrohungen durch Fressfeinde und Konkurrenz um Futter. Am besten beginnt man mit einer ansehnlichen Gruppe, um ein natürliches Geschlechterverhältnis zu gewährleisten und die soziale Interaktion zu fördern, was eine Voraussetzung für die Zucht sein kann. Sobald ein Weibchen „eiertragend“ ist, wird es die Eier mehrere Wochen lang befächeln und säubern, bis sie schlüpfen. Die frisch geschlüpften Junggarnelen sind unglaublich klein und werden nicht aktiv schwimmen, um Futter zu finden. Stattdessen weiden sie auf jeder Oberfläche, auf der sie landen. Daher muss das Aquarium gut etabliert und eingefahren sein, mit einer dicken, gesunden Schicht aus Biofilm und Algen, die alle Oberflächen bedeckt. Dies ist ihre primäre Nahrungsquelle, und ohne sie werden sie verhungern. Obwohl spezielles, feines Staubfutter für Jungtiere als Ergänzung angeboten werden kann, kann es die Notwendigkeit von reichlich vorhandenem, natürlich vorkommendem Biofilm nicht ersetzen, um eine hohe Überlebensrate bei den jungen Garnelen zu gewährleisten.

Druckbare Karte erstellen

Erstellen Sie eine druckbare Karte für dieses Tier zur Anzeige in Ihrem Geschäft oder Aquarium. Die Karte enthält einen QR-Code für schnellen Zugriff auf weitere Informationen.